MARCEL VAN DER MEIJS

Urban designer, Palmbout Urban Landscapes

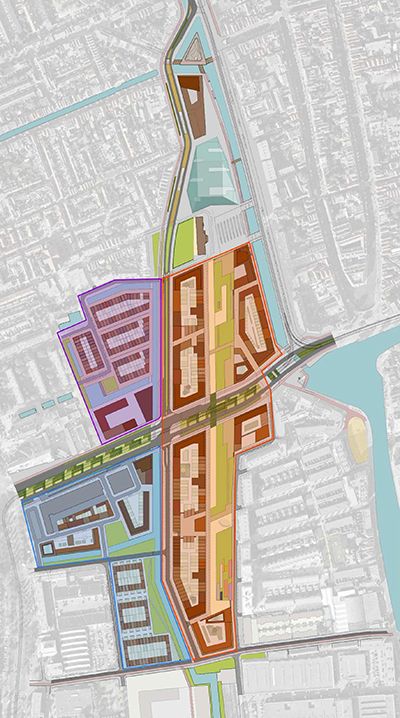

Presently, a 2,3 km cleft runs through Delft. As part of a massive transformation of the city, the railtracks are brought underground, opening up a significant amount of land for new development. The spoorzone lies at the heart of the city, but is a tabula rasa after this transformation. How does one design, given this post-infrastructural situation? Students in the spoorzone-workshop used routes, phasing and structural elements as possible solutions. How are those implemented in the actual context? To answer these questions, Atlantis interviewed Marcel van der Meijs of Palmbout Urban Landscapes who is currently working on the urban masterplan for Spoorzone Delft.

The spoorzone is a really specific kind of assignment. The site, the context, it is all defined by infrastructure, but this is no longer visible. What are the characteristics of this situation?

The spoorzone is a really specific kind of assignment. The site, the context, it is all defined by infrastructure, but this is no longer visible. What are the characteristics of this situation?

The railtracks always have defined the area. Now, the tracks are placed underground, so it has completely disappeared, leaving a void in the city which you try to fill like it was never there. It is quite special to have such a large area in the city center devoid of space and function. Around the station, houses had to be demolished, but mostly it was a lot of empty land, because rail tracks require so much land. This gives you space to reintegrate the city.

Are there other characteristics?

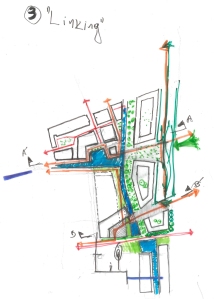

Orientation. Delft has always placed its backside to the railway strip. Now the city wants to direct itself to it. No longer is it a sound-nuisance, so it can start to fulfill a real urban function, perhaps comparable to the market. This transformation, from backside to frontside, can happen in more places: The ‘Voorhof’, for example. Also, the urban fabric has always been very limited by the railway tracks,especially in the southern part. The northern part was elevated by a viaduct, so a high degree of permeability was achieved. This was one of our reasons to use [east-west] routes as a starting point to expand the urban fabric and to weave it together, to get to a situation which is brought closer together.

Your answer to the situation suggests giving the space more of a city-feel, right?

Yes, it needs to become a part of the city by attaching it to adjoining city districts. Not only do you use the urban fabric, but also with the buildings and the inhabitants who will want to live there. It is designing the context, using the context to bring the city together.

Aiming to reintegrate the city, many student proposals use connections and routes. How does Palmbout’s plan uses them?

Aiming to reintegrate the city, many student proposals use connections and routes. How does Palmbout’s plan uses them?

The informal is really important: not focusing on cars, but giving cyclists and pedestrians more opportunities. The building blocks have breakthroughs, so people traversing the area are offered many different routes, which are not there now. They can follow the canal or go through the park. They go in the direction of the station or of the Schie. There is a rich variety of routes, especially routes for cyclists and pedestrians.

Phasing also came up in the students’ plans. This is a large-scale project many risks of failure. How you deal with this in the spoorzone?

We want to make a plan that is robust and can react to many changes in society and the market. Therefore, the blocks are highly adjustable, and this gives you the means to be very flexible in phasing. The different demands are given different opportunities in the phasing.

Secondly, the question is when areas are free to be built, because work on the tunnel will continue for a long time. And then, which areas do you want to build? The area close to the Voorhof will be available soon, but it is the furthest most point from the city center. You want a smart way of building your plan to make the right ambiance. You want to get the feeling that if you start at the station, you want to conquer the area from there and make a new vision of Delft.

Secondly, the question is when areas are free to be built, because work on the tunnel will continue for a long time. And then, which areas do you want to build? The area close to the Voorhof will be available soon, but it is the furthest most point from the city center. You want a smart way of building your plan to make the right ambiance. You want to get the feeling that if you start at the station, you want to conquer the area from there and make a new vision of Delft.

You talked about the phasing of the ‘final’ plan. But what do you think about the temporary use of the spoorzone?

Currently, there are many initiatives. Temporariness, which we are talking about, should be designed because initiatives will last for a couple of years, and they should be fitting for the location. So at the station area, which needs to be developed at a later stage, you can organize something relatively long lasting with a high degree of urbanity.

What significance does temporary use have in the plan?

Temporary use can set an ambiance, ‘we are making a city’. We do not know what specific kind of use, but there are many initiatives: urban agriculture, city greenhouses, viewing towers or festival areas. Those should be used to set the groundwork for the area,to make the area part of the city. Thus phasing and temporary use are heavily interconnected.

Do you have a strategy to deal with the initiatives?

We do not program it, but we are part of a long term conversation. I think that the municipality of Delft should take up the main responsibility for this. As a design office, we can put this on the agenda though. Phasing mostly deals with buildings, but is also about the public space.

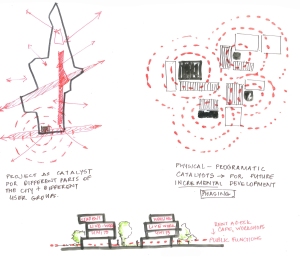

The final tool used in the student proposals is cornerstone elements, or, interventions that influence the complete area. What are some examples of these in the Palmbout plan?

The water structure and the park [are our cornerstone elements], forming two long lines. The Nieuwe Delft starts at the station like a ‘gracht’ and turns greener with softer edges. And like the water in the city center, it goes everywhere, connecting everything. And the park-the park itself is actually not that big, about 30 meters wide,ut it is a long space, and it is giving Delft something new.

The plan itself calls for ‘provoking elements’. How does this work?

The plan itself calls for ‘provoking elements’. How does this work?

Well, you offer possibilities to realize a certain program. On the one side you draw an attractive cityscape, on the other side you make someone feel fitting in an area. So we make collages, showing what kind of city this can be. People then can meet this challenge, actually realizing it, but in their own way, within certain boundaries. The provoking itself it based on making an area attractive to live,. and showing the many possibilities of how people can work and live there.

In working on the plan for the spoorzone, what were your methods?

We draw a lot. You try to find the lines which fit logically in the area. You try, starting in the public space, to draw a way in which it all comes together. You do this again and again, until it fits nicely.

While drawing you try to imagine the public space. Should it be part of the city center, finely grained? Or more modernistic? And while you draw, you get closer and closer to the image in your mind. For example, if you make a ‘gracht’, the distance to the water determines how you experience it. So this had consequences for the way the height levels interact.

As a closing question, how do you define infrastructure?

The first images springing to mind are large scale constructs like roads. But it is actually so much more. It is above and below the surface, it is between people and how they live together. It is a broad definition, perhaps, having more to do with connecting.

And in the spoorzone, what is the defining infrastructure?

The structures below grounds: there lies the most important railway in the Netherlands. But in our design, the Nieuwe Delft, Not so much the road but the water and its edges, is the binding element. It should be more than just a road, but also a popular public space that people really use. Because it ties everything together, everything is attached to it. It binds the outer borders with the city center. It is the axis of the area.