MATTHIJS VON OOSTRUM & ANDREW REYNOLDS

TU Delft Urbanism Graduates

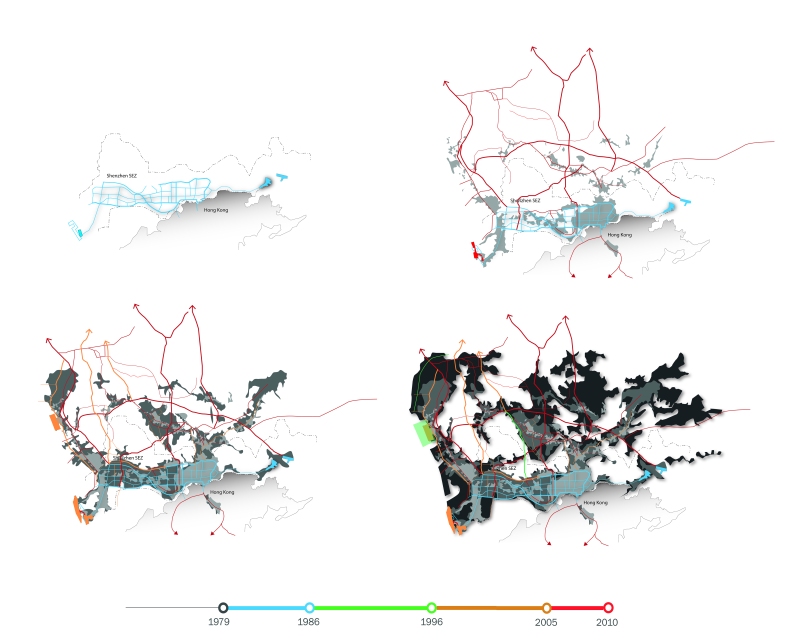

Nowhere else could there be a more intriguing juxtaposition of hard and soft infrastructure than in the Chinese city Shenzhen, which rocketed from a small fishing village of 30,000 people to a mega city with a population of approximately 14 million in only 30 years[i]. However, following rapid economic growth and the ensuing urbanisation, Shenzhen is now at a cross roads. The previously successful approach of economic growth at all costs has to be reconsidered to better address the needs of local residents and the migrant population and there is need to engage with specific local conditions and new forms of planning (Friedmann, 2004). Commencing in September 2012, eight students from the Complex Cities studio (TU Delft Urbanism) agreed to take on this challenging city in the graduation studio Shenzhen Scenario’s led by Dr. Stephen Read, Dr. Diego Sepulveda and Dr. Lei Qu.

The urban development of Shenzhen is shaped by two intertwined rationalities. The first has been driven by the Municipal and National Governments pursuit of economic growth, where urban planning and the development of infrastructure has been a tool of the political economic development program (Chen, 2010). The second is the associated urbanisation process, a by-product of the economic growth that resulted from the arrival of millions of migrant workers, the development of local industries, local economies, and the daily life of the residents.

Urbanisation: A product of economic growth

In 1978, Deng Xioping instituted the ‘Opening up policy’, which led to the creation of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ), an area of relaxed financial regulation and increased local Government autonomy, which was designed to encourage foreign direct investment. The urban development of the city was guided by an approach of infrastructure led urban planning. This policy was extremely successful with an annual GDP growth rate of 38.9% between1980 to 2001 (Ng, 2003).

In 1992, Deng Xioping introduced further reforms allowing the paid leasing of land use rights by the Municipal Government. This had the desired effect to further stimulate the economy, but it also created a land based economic development model. This land based approach provided a valuable source of income for the local government, but caused land price spikes and the development of a land rent gradient in urban areas. This system encourages projects that will achieve high financial returns in well located urban areas, often to the detriment of the existing urban residents as cities are considered to be capital for making profit by the Government, businesses and developers (Ye, 2012).

The Regional Infrastructure

Shenzhen is now being redefined by new urban scales and increasing levels of competition. The cities of the Pearl River Delta (PRD) have an estimated combined population of 27 million people (Woetzel et al. 2009). Driven by the National and Municipal Governments’ aims to develop an urban agglomeration to improve economic competiveness and innovation these cities are becoming increasingly connected by major regional infrastructure. At the same time, competition between the cities in the PRD, as well as intra-urban competition between city districts, intensifies.

The city is also currently caught up in China’s infrastructure fever with new metro lines planned to outer areas and a new high speed rail connection to Guangzhou constructed. The rapid development of the metro network has been another major factor in driving economic growth and urban development. The development of the metro is counted as local infrastructure investment, improving the figures of local economic growth, while also increasing land prices in the areas adjacent to the new stations. The arrival of new stations has catalysed a series of new development projects, however, the new stations have also created a number of local problems and displaced the existing residents.

The logic of the urban village

A significant source of income for the Shenzhen Municipal Government is the leasing of land use rights, which has led to the creation of a land-based economic development model. For example, large urban projects are attractive to the government as they provide instant economic progress and demonstrate rapid urban transformation. However, the development of these projects does not address the needs of the existing local residents. There is, however, another logic to the development of Shenzhen and that is the logic of the migrant. Shenzhen is principally a migrant town and for the last four decades, people from the Chinese interior have flocked to the city in order to find work in the factories. Many of the migrant workers in Shenzhen are living in so called urban villages (Chengzhongcun) which were created when the expanding city engulfed existing rural villages. The urban villages then developed into housing and commercial areas with a distinctive seven storey typology providing affordable housing for the city workers. The arrival of migrants created an opportunity for the landlords of the villages sited around the original SEZ. The migrants and the landlords influence each other in a positive cycle; landlords offer housing and space for businesses and the migrants rent these spaces and raise the revenue of the local shops and industries. This new revenue allows the landlords to make new investments and the cycle starts again.

Local soft infrastructure

The urban villages are no black boxes that magically turn poor rural migrants into affluent middle class. The villages offer a soft infrastructure that is key to the socio-economic upgrading process. The land in the villages is communally owned by the landlords who manage their land in village committees. Similarly to many other arrival cities, migrants from different regions in China cluster in different parts of the city, although this can be difficult for foreigners to notice. The social ties from a migrant’s home region often transfer to the urban villages and can play an important role in local integration. If not for these social structures, life in the villages would be very difficult. Without local city rights the migrants have no access to public services, so the landlords also provide education, healthcare and child support (against payment). The local soft infrastructure used by the migrants manifests itself in very real hard infrastructure. The ancestral hall, which still exists in most urban villages, is the place where the village elders come together, play cards, and discuss the future of the village. In the informally constructed market hall, people meet, trade, socialize and engage in commerce. The piece-by-piece growth of the village around a centuries old urban fabric allows a natural connection between all these spaces.

Studio work

Understanding how the local soft infrastructure operates and its relationship to the hard infrastructure forms a key area of investigation for the graduation studio. In the research that we undertook, it become clear that the spatial demands of local residents and migrants rarely align with the financial demands of the government and developers. Generally, the projects argued for a more endogenous planning approach from the perspective of the current inhabitants. In our descriptions, we show that the value of existing spaces is greater than the mere price of the land. Most of the designs did not represent final answers or projects that could be readily implemented, rather the designs considered what elements should be taken into consideration, who should be involved in the development process, and developed strategies to better integrate the different demands.

Conclusion

The issues raised in this article provide a snapshot of some of the questions that the studio has been dealing with and the relationship of the projects to the hard and soft infrastructure. It has become clear from the projects that there needs to be more effort in connecting the regional scale economic demands for increased growth and improved competiveness with improving the local scale urban environment and living conditions, particularly for the low income workers and migrant residents of the city. The urban planning of Shenzhen is famous for its innovation and agility. As Shenzhen moves into its fourth decade, the challenge now is how it move from the successful economic growth led urban development model focussing on hard infrastructure, to one that includes the existing inhabitants and focuses more on the soft infrastructures necessary for an inclusive city.

Chen, Z. (2010). The production of urban public space under Chinese market economic reform – A case study of Shenzhen. The University of Hong Kong.

Friedmann, J. (2004). Strategic spatial planning and the longer range. Planning Theory & Practice, 5(1), 49–67

Ng, M. K. (2003). Shenzhen. Cities, 20(6), 429–441

Woetzel, J., Mendonca, L., Devan, J., & Negri, S. (2009). Preparing for China’s urban billion. McKinsey Global Institute, …, (March).

Ye, L. (2012). Promoting integrated metropolitan governance: The case of the Pearl River Delta. In Governing the Metropolis: Powers and Territories. Paris.

Zacharias, J., & Tang, Y. (2010). Restructuring and repositioning Shenzhen, China’s new mega city. Progress in Planning, 73(4), 209–249

[i] Officially 7 million plus an estimated 7 million ‘floating population’ according to Zacharias & Tang, 2010