DR. ARIE ROMEIN & DR. JAN JACOB TRIP

Researchers, OTB, TU Delft

Due to economic restructuring and technological advancement in the last decades the way that people live, work and connect to each other has irreversibly changed. The development of a wide range of new economic activities, mainly concerned with the generation or exploitation of knowledge and information e.g. creative industries, have affected the organization of the metropolitan, national and global networks. The following article focuses on these issues by exploring some major creative economy notions in combination with ‘networked urbanism’ concept of Gabriel Dupuy (1991). The latter defines the city as a territorial organization, made possible by the urban networks of transport and telecommunication, production and consumption through which people experience urban life.

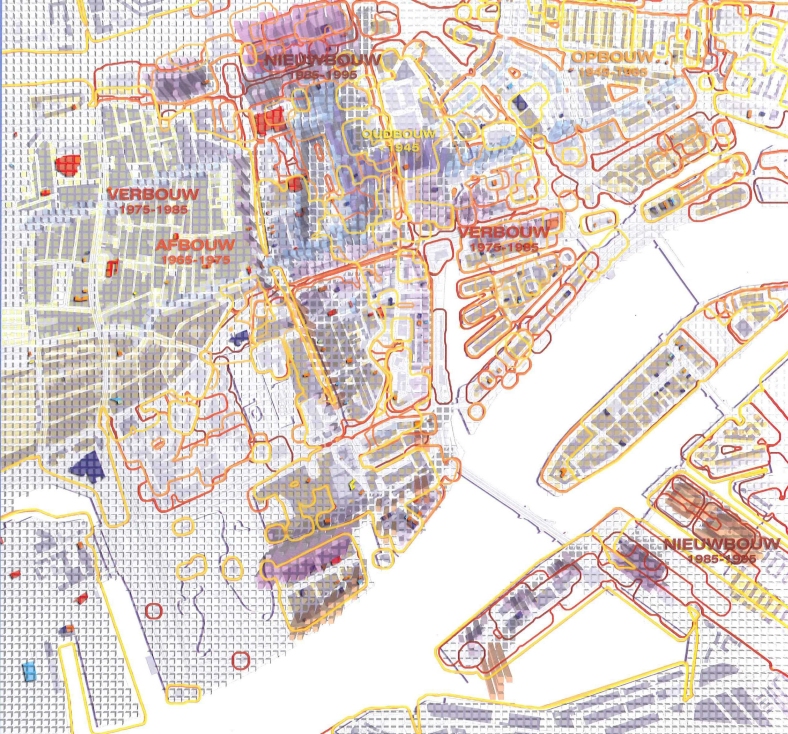

Figure 1. Cultural Production x Transformation of Real Estate x Rental price in €m2 in Atlas of Cultural Ecology, Rotterdam.

Scenes and businesses

‘It’s in the air’. Thus described Alfred Marshall (1920) the local atmosphere of competitive clusters of related economic activities about a century ago. This is particularly true for the creative economy. Much creativity flourishes in scenes that are rather invisible and intangible, like being in the air, for firms in the mainstream economy. Still, if unveiled, fruits of creativity which range from basic ideas to, occasionally, prototypes may be turned into concrete innovations.

Some scholars explicitly suggest that such hidden creativity could potentially be transferred into innovative commercial products and services produced by firms in the formal mainstream economy (e.g. Currid 2007; Zukin 2010). This is elaborated most explicitly by Cohendet et al. (2010) who distinguish 1) the ‘underground’ which contains the informal local scenes; 2) the ‘upperground’ where we find the firms that (may) utilise the ideas generated in the underground; and 3) the ‘middleground’; an amalgam of actors, communities, venues and amenities which is supposed to connect the underground and the upperground.

Underground subcultures and scenes often harbour a lot of creativity but are hardly focused on practical use or on commercial exploitation. Nevertheless, there are quite a few examples of ideas from subcultures influencing product development in the upper ground, and even of scene members cooperating with regular businesses; think of the long-standing impact of the hacker subculture on software development and ICT security (Flowers, 2008) or the influence of youth subcultures on mainstream fashion design (Frank, 1998). The extent to which creativity generated in local scenes can be transferred to clusters of firms – mostly small and medium-sized ones – to be utilised in innovations and new products or services, depends on both strong and weak ties within and between these scenes and firms. Ever since Granovetter’s classic study The Strength of Weak Ties (1973), “the power of weak ties has been lauded in sociology and network theory” but “strong ties have a vital place too” (Zolli and Healy, 2012, pp. 245 – 246).

Power of weak ties

Small and clearly demarcated networks of more or less congenial actors tend to be connected by strong ties, while weak ties provide bridges to actors who are not or less well connected. Strong ties are found within firms or business clusters in the upper ground where they are essential to incorporate external information and knowledge into innovations, as well as in subcultures and scenes in the underground with their often tight communities. It is in particular the middleground, however, that provides opportunities for the weak ties that are essential to transfer ideas emanating in the underground to the upperground. In the middleground these are often the source of ‘out-of-the-box’ breakthroughs that inspire new ideas in rather unexpected ways (Campbell, 2012).

Gaining insight in how these relations are structured and how ideas are transferred from local scenes through the middleground to mainstream firms may contribute to our understanding of the local ‘ecosystems’ for innovation. However, problematic is the tendency for many connections going through the middleground to be not just weak, but also largely invisible. This makes it quite difficult to get a clear idea of the ‘missing links’ between the upperground and the underground. Who connects to who, what exactly is the connector, what determines the shape of these connections, and how does the actual transfer of ideas take place? And, one step further, can we identify cases where a connection may be expected but does not show up?

Dupuy’s model

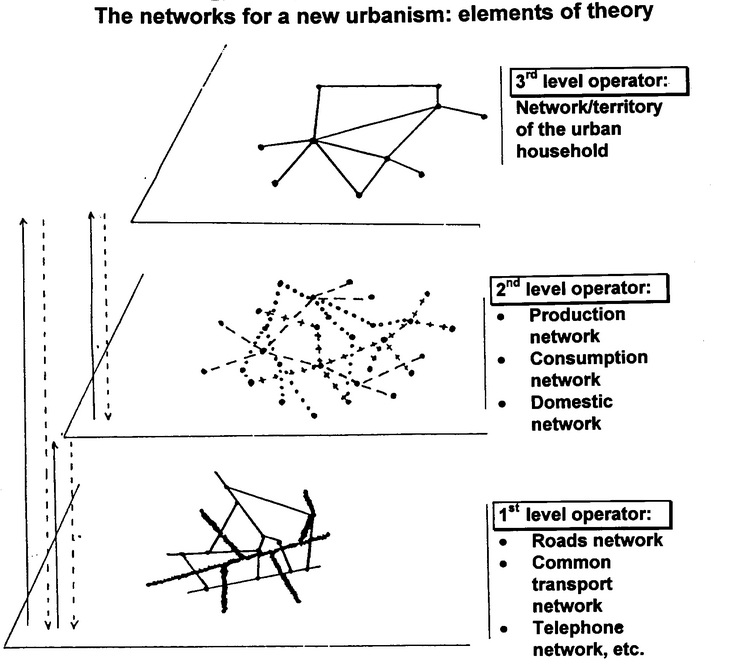

Terms like underground and upperground suggest a layered structure. Triggered by the focus of this issue of Atlantis, we therefore confront the above ideas on the creative economy with the model of ‘networked urbanism’ by Gabriel Dupuy (1991), which presents a layered structure of ‘level operators’, i.e. the urban networks of transport and telecommunication, production and consumption. Can Dupuy’s model shed a new light on the less tangible interactions between the underground and the upperground?

Compared to the networked urbanism of Dupuy, a networked urbanism of the creative economy is focused less on physical links such as roads and cables – although especially the latter remain important to facilitate transport and communication – than on the nodes where people and knowledge come together and are exchanged. These nodes consist of ‘hard’ infrastructure (e.g. educational institutions, laboratories, cultural venues, meeting places and amenities) as well as ‘soft’ infrastructure (e.g. social media, events, curricula of education and organisations such as interest groups or professional associations. Quite a few of these belong to the middleground as defined by Cohendet et al. (2010).

The first level operator in Dupuy’s model – infrastructural networks – is characterized by a firm hard infrastructure in the upperground, consisting of ICTs, office buildings and planned knowledge locations, but also by theatres and restaurants. In the underground, on the other hand, hard infrastructure tends to be of a generally smaller scale and less dependent on sizeable long-term investments. This is usually true for the pubs and clubs where scene members meet, but also for the places where they work and live. Whereas large firms or universities tend to own considerable amounts of real estate and equipment, many scenes and subcultures typically do not own the venues where they work and meet. Instead, they often rent or squat places, always on the look-out for cheaper alternatives, making them rather ‘footloose’.

Opportunities for connecting individuals and networks, the other two level operators in Dupuy’s model, in the upperground and the underground are not just defined by their respective hard and soft infrastructures. Scenes and subcultures on the one hand, and firms and business clusters on the other, are likely to use largely (if not completely) different infrastructures. Interaction may take place where these respective infrastructures overlap: directly (the underground hacker and the ICT professor meeting at the computer fair) but more likely indirectly by a number of intermediate steps (the hacker meeting a fellow hacker, who contributes to a computer magazine, the editor of which talks to the ICT professor). The main part of these linkages take place in the middleground of physical meeting places such as pubs, college rooms and outdoor amenities, but also events and digital platforms such as LinkedIn, where people gather in particular groups, or the organisations of which they are a member.

In the end, the mutual impacts of interaction between underground and upperground depends on who meets who. In this regard, it is decisive which specific venues, events or platforms are visited mostly by members of which actor groups and which networks in both the underground and the upperground. Scenes connote specific places and venues where likeminded assemble and meet. They value these places for the performance with and to one another (authenticity), for being ‘on stage’: seeing and being seen (theatricality), and for shared senses of what is right (legitimacy). At the other end of the spectrum, there is the often small circle of restaurants and cafés where managers and politicians meet and talk. The aggregated pattern of individuals’ norms and values thus define the places where the members of a group know they can expect to find each other. These norms and values more or less resemble the vertical arrows that connect the levels of Dupuy’s model.

Summing up, it may be said that weak ties between people representing networks in both underground and upperground establish in certain physical or digital places in the middleground where they (1) can meet and (2) actually go to and do meet. Dupuy’s model may be useful in the analysis of where exactly this interaction between underground and upperground occurs, which may help to reveal successful transfer of creativity and ideas and to identify bottlenecks and lacunas in the middleground that hinder or block such transfer. Both may be relevant for local and region planners and policymakers who aim to strengthen the innovative capacity that is considered crucial for the competitiveness of their city or region.

Putting it into practice

To the best of our knowledge, empirical studies that analyse the ties between upperground and underground from a perspective as described above do not exist yet, nor do policies that explicitly and systematically aim to establish such ties. Nonetheless, some examples may be mentioned of projects that, at least in some aspect, suggest such a line of thought.

The project 3×3 in Oldenburg (Germany) starts from the idea ithat artists open up new perspectives and ‘outside the box’ ways of thinking to companies in mainstream branches. Three teams, each composed of three artists or creative entrepreneurs (stage actors, industrial designers, photographers etc.) and three employees of a formal company in whatever non-creative branch, work together for four weeks to solve an internal problem of the company. The problems discussed may be about all kinds of issues, for instance regarding the company strategy, staff issues, logistics, product renewal or marketing. This method effectively brings together the underground and upperground, although it involves somewhat ad hoc meetings of individuals in specific locations rather than establishing lasting ties between different networks. In a way, it jumps from Dupuy’s 3rd level operators directly to the infrastructural level.

The Atlas of the Cultural Ecology is an example that, at least graphically, resembles Dupuy’s model. It is published by the Municipality of Rotterdam in 2004 (Gemeente Rotterdam, 2004). It contains three sets of different maps that can be layered over one another. These are (1) basic maps showing the degree of public accessibility of places during the day and at night, (2) functional maps showing e.g. types of shops, nightlife and cultural venues, event locations and knowledge infrastructure, and (3) ‘perspective’ maps of for instance movement flows of people, building periods, policy areas, real estate values, public safety, ethnicity and parochial domains. They combine detailed information from various levels of Dupuy’s model, starting with types and location of venues where people meet, the 1st level operator. This followed by information on who are expected to go where, why and when. The ethnicity and parochial domain (who), the accessibility, public safety (why) and the day, evening or night (when) fit in Dupuy’s other two level operators. These rather unique maps provide much information about ‘how the city works’. Sadly the analysis was never continued, and a clear connection to policy is lacking.

As these example of underground scenes and upperground businesses shows, models such as Dupuy’s can structure the analysis of the creative economy. However, it cannot identify where the weak ties between the underground and the upperground occur. Therefore, detailed research remains needed to disentangle the networks and interactions through the middle ground.

References

Campbell, T. (2012): Beyond smart cities; how cities network, learn and innovate. Earthscan, London & New York.

Cohendet, P., D. Grandadam and L. Simon (2010): The anatomy of the creative city. Industry and Innovation, 17(1), 91-111.

Currid, E. (2007): The Warhol economy; how fashion, art and music drive New York City. Princeton University Press, Princeton/Oxford.

Dupuy, G. (1991): L’urbanisme des réseaux; théories et méthodes. Armand Colin, Paris.

Flowers, S. (2008): Harnessing the hackers: the emergence and exploitation of outlaw innovation. Research Policy, 37(2), 177-193.

Frank, T. (1998): The conquest of cool: business culture, counterculture, and the rise of hip consumerism. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Gemeente Rotterdam (2004): Sense of place; atlas van de culturele ecologie van Rotterdam. Rotterdam

Granovetter, M.S. (1973): The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

Marshall, A. (1920): Industry and trade; a study of industrial technique and business organization; and of their influences on the conditions of various classes and nations. MacMillan, London.

Silver, D., T.N. Clark and C.J. Navarro Yanez (2011): Scenes: social context in an age of contingency. In: T.N. Clark (ed.): The city as an entertainment machine [revised ed.], Lexington Books, Lanham MD.

Zolli, A. and A.M. Healy (2012): Resilience. Headline Publishing Group, UK.

Zukin, S. (2010): Naked city; the death and life of authentic urban places. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

2 thoughts on “A LAYER-MODEL PERSPECTIVE ON THE CREATIVE ECONOMY”